Contemporary Uses of Tibetan Sound Healing Techniques

Published on May 7, 2017.

Last updated on May 7, 2017.

Written by Chad Timblin.

A variety of sound healing techniques have been developed in the region of Tibet throughout its long history. This paper will explore a few ancient Tibetan sound healing practices that are still being employed today, such as mantra chanting, singing bowl meditations, and other sacred rituals.

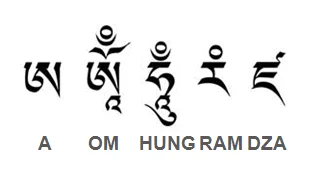

The human voice is one of the most primal instruments used to make music and it has the potential to elicit inner healing in individuals who intentionally use their vocal cords to produce certain vibrations. Bön Buddhism, which is the oldest spiritual tradition in Tibet, recognizes Five Warrior Syllables that contribute to inner healing in specific ways when they are chanted in a meditative manner (Rinpoche vii). The Five Warrior Syllables are: A, OM, HUNG, RAM, and DZA. The term warrior is used to refer to the practitioner's ability to "conquer the forces of negativity" (Rinpoche 8). The Five Warrior Syllables are also known as "seed" sounds because they contain in them the seeds of enlightened qualities (Rinpoche 5). These enlightened qualities are collectively referred to as the Four Immeasurables in the Tibetan Bön Buddhist tradition, which are love, compassion, joy, and equanimity (Rinpoche 10).

According to Tibetan Bön Buddhism, every person is innately pure—even if it does not seem so due to conditioning—and the practice of chanting the Five Warrior Syllables naturally leads to the awakening of one's true nature which intrinsically contains the Four Immeasurable Enlightened Qualities (Rinpoche 10). Tibetan Bön Buddhist master Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche says: "With sound, we clear our habitual tendencies and obstacles and connect with the clear and open space of our being"

(Rinpoche 5). It is important to note that if one wants to successfully achieve inner healing and uncover their innate enlightened qualities with the help of these seed sounds, consistent practice must be prioritized over intellectual theorizing, which has the potential to distract one from actually doing the necessary work that leads to healing. A common cause of suffering is over-identification with one's constantly fluctuating mental activity; chanting leads to the cessation of mental clutter and the uncovering of one's innately clear awareness.

Seed syllables

Seed syllables

Traditionally, each seed syllable is chanted in sequence, from A, which leads to the discovery of clear, internal space, to DZA, which brings about spontaneous manifestation of enlightened qualities. Each syllable corresponds to an energy center, or chakra, in the body that can be focused on when one chants to connect with the particular quality that corresponds with that syllable (Rinpoche 5). Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche says: "By simply drawing our attention to a chakra location, subtle prana is activated. Prana is the Sanskrit word for 'vital breath'; the Tibetan word is lung, while the Chinese use qi or chi, and the Japanese, ki... Through the vibration of the sound of the particular syllable, we activate the possibility of dissipating physical, emotional or energetic, and mental disturbances that are held in the prana, or vital breath"

(Rinpoche 7). Another step to the technique is to visualize light in the colors that correspond with each syllable / chakra (Rinpoche 7).

There are different chakra systems found in different cultural traditions; Bön Buddhism recognizes five main chakras/energy centers in the body:

- The seed syllable A is associated with the forehead and crown chakras, the changeless body, and white light;

- OM is connected to the throat chakra, the quality of unceasing speech, and red light;

- HUNG to the heart chakra, the quality of undeluded mind, and blue light;

- RAM to the navel chakra, ripened virtuous qualities, and red light;

- DZA to the secret chakra, spontaneous action, and green light.

There are three main kinds of obstacles that can be cleared by the practice of chanting these Five Warrior Syllables (Rinpoche 8):

- outer obstacles (e.g. sickness and other negative circumstances),

- inner obstacles (e.g. negative emotions),

- secret obstacles (e.g. harder to understand, subtle, or hidden obstacles connected to doubt, hope, and fear).

In addition to chanted mantras, the use of singing bowls is a sound healing technique that has been present in Tibet since Buddhism was introduced to Tibet by Padmasambhava, a great Buddhist master, in the 8th century A.D. (Shrestha 19). Like the practice of the Five Warrior Syllables, Tibetan singing bowl therapy recognizes that stress and negativity can lead to energy blockages within a human's vibrational field. Suren Shrestha, a sound healer who has studied Tibetan singing bowl therapy extensively, says: "Sound and vibration can be used to re-tune us to health and one of the most powerful modalities for this is the use of Tibetan singing bowls. When there is a deep relaxation through soothing, resonant sound, the body is affected on a cellular level, opening up the flow of energy to move us back toward vibrational alignment with health"

(Shrestha 19).

Padmasambhava

Padmasambhava

Modern quantum physics has scientifically demonstrated that everything has a vibration (Shrestha 14). Matter that is apparently static is actually, from a physicist's perspective, a particularly dense form of energy vibrating at a relatively slow speed. In other words, "matter is the explicate particle reality which has unfolded from the purely energetic wave aspect of reality that David Bohm called the implicate order"

(Fruehauf). The sound vibrations produced by Tibetan singing bowls interact with the vibrations that make up a human body and catalyze the body and mind to reach higher levels of vibrational harmony. The human body is made up of as much as 70% water, which can be directly affected by the vibrations produced by singing bowls. According to Suren Shrestha, "when you strike a singing bowl next to your body, the vibration makes a mandala (a pattern) in your body, which is healing and relaxing"

(Shrestha 15). Mitchell Gaynor, M.D. says: "You can look at disease as a form of disharmony. And there's no organ system in the body that's not affected by sound and music and vibration"

(Campbell 102).

Suren Shrestha administering a singing bowl healing session.

Suren Shrestha administering a singing bowl healing session.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead, an ancient manual for navigating the state between death and rebirth, includes descriptions of a number of internal sounds experienced by a recently deceased person at various points in their journey through the afterlife bardos (i.e. transitional states between life and death). The experiences of ancient Tibetan lamas who trained their consciousness to intentionally navigate the various bardos informed Tibetan Buddhist beliefs about the relevance of sound on the earthly plane. Tibetan lamas recognize certain sounds that they believe naturally occur as internal perceptions when one puts one's fingers in one's ears to block out the sounds of the external world: clicking, thudding, clashing, soughing, ringing, tapping, moaning, and shrill whistles (Leary 23).

"Tibetan lamas, in chanting their rituals, employ seven (or eight) sorts of musical instruments: big drums, cymbals (commonly brass), conch shells, bells (like the handbells used in the Christian Mass Service), timbrels, small clarinets (sounding like Highland bagpipes), big trumpets, and human thighbone trumpets. Although the combined sounds of these instruments are far from being melodious, the lamas maintain that they psychically produce in the devotee an attitude of deep veneration and faith, because they are the counterparts of the natural sounds which one's own body is heard producing when the fingers are put in the ears to shut out external sounds. Stopping the ears thus, there are heard a thudding sound, like that of a big drum being beaten; a clashing sound, as of cymbals; a soughing sound, as of a wind moving through a forest – as when a conch-shell is blown; a ringing as of bells; a sharp tapping sound, as when a timbrel is used; a moaning sound, like that of a clarinet; a bass moaning sound, as if made with a big trumpet; and a shriller sound, as of a thigh-bone trumpet" (Leary 23).

This practice produces a cacophonous result compared to the soothing tones produced by homophonic mantra chanting and resonant singing bowls. However, Tibetan lama practitioners of this technique maintain that the chorus of instrumentally-induced sounds catalyzes healing due to its correlation with internally-produced sounds of the human body.

The aforementioned Bön Buddhist tradition is the earliest traceable source of many Tibetan chanting styles (Goldman 69). A mysterious chanting phenomenon referred to by researchers of the Tibetan tantric tradition known as the 'One Voice Chord' is a fundamental aspect of Tibetan Buddhist spiritual practice. Dr. Huston Smith, a Tibetan scholar, described elements of this Tibetan chanting style: "They discovered ways, we still don't know how, of shaping their vocal cavities to resonate overtones to the point where these became audible as distinct tones in their own right. So each lama thus trained could sing chords by themselves. They are singing D, F# and A simultaneously"

(Goldman 66). The spiritual significance of this practice for Tibetan monks who have been initiated into the tradition is related to the goal to invoke certain deities and then unite their consciousness with the consciousness of the chosen deity. Huston Smith posited that the chanting may be used by monks to help shift their awareness from the mundane to the spiritual and to consequently embody the divine characteristics of love, compassion, joy, and equanimity (Goldman 69). The Tibetan tradition of chanting the 'One Voice Chord' is still very much alive and cannot adequately be explained in words—one needs to experience the resonant sounds first hand—through a recording or in person—to more meaningfully and directly understand their healing potency.

A thread uniting the various sacred Tibetan practices involving sound and vibration is the common goal to increase one's state of harmony through direct participation in the practices and to awaken the innate qualities of love, compassion, joy, and equanimity. Various forms of chanting, singing bowls, and choruses of cacophonous sounds to mirror the body's internal sounds have been, and continue to be, used by Tibetan practitioners as tools to fight against forces of negativity. Success in dispelling negativity is closely related to the conscious severing of attachment to one's limited egoic tendencies and openness to accepting what is, rather than identifying with constantly fluctuating mental phenomena that have a tendency to create unnecessary suffering.

Works Cited

Campbell, Don G., and Alex Doman. Healing at the Speed of Sound: How What We Hear Transforms Our Brains and Our Lives. New York, NY: Plume, 2012. Print.

Fruehauf, Heiner. "Cultivating the Flow: A Concept Of Evolutive Well-Being that Integrates the Classic Traditions and Quantum Science." ClassicalChineseMedicine.org. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Apr. 2017.

Goldman, Jonathan. Healing Sounds: The Power of Harmonics. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts, 2002. Print.

Leary, Timothy, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert. The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. N.p.: Citadel, 2000. Print.

Rinpoche, Tenzin Wangyal. Tibetan Sound Healing. Louisville, USA: Sounds True, 2011. Print.

Shrestha, Suren. How to Heal with Singing Bowls: Traditional Tibetan Healing Methods. Boulder, CO: Sentient Publications, 2013. Print.