Douglas Harding's 'The Headless Way'

Published on April 24, 2019.

Last updated on April 24, 2019.

Written by Chad Timblin.

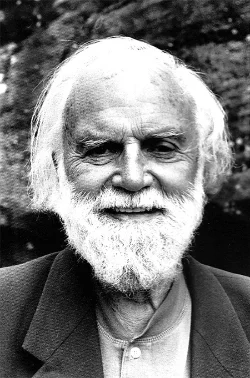

Douglas Harding (1909-2007)

Douglas Harding (1909-2007)

Douglas Harding was a scholar/philosopher who experienced mystical awareness himself, which informed his theories about mystical experiences. He writes about a state he refers to as 'headlessness,' which is a present-immersed state of perceptual clarity, free from identification with thoughts. His experience of 'headlessness' made him realize that he was not who he thought he was: "[This hole where my head should have been] was a vast emptiness vastly filled, a nothing that found room for everything... I had lost a head and gained a world... utterly free of 'me', unstained by any observer. Its total presence was my total absence, body and soul. Lighter than air, clearer than glass, altogether released from myself, I was nowhere around" (Harding 6). In other words, Harding woke up from the dream of everyday life, which usually entails identification with one's thoughts as representative of reality, and clearly experienced an awareness unconditioned and unaffected by mental activity.

Harding wrote that when people use their present, immediate experience as evidence for their identity rather than hearsay from other people or their own imagination, one incontrovertibly discovers that one does not possess a head. Everything that can be experienced in the phenomenal field of awareness, including physical sensations of the body, are "swallowed up in the abyss at the center of [one's] being" (Harding 9). Harding wrote that anyone can reconnect to their inherent emptiness, free from identification with a transitory mentally-derived ego. According to Harding, all it takes is "alert naivety..., an innocent eye and an empty head (not to mention a stout heart) to admit [one's own] perfect emptiness" (Harding 9).

Harding created a theoretical map (dubbed the 'Headless Way') of what he believed were the eight major stages of development for a human being: (1) The Headless Infant, (2) The Child, (3) The Headed Grown-up, (4) The Headless Seer, (5) Practicing Headlessness, (6) Working It Out, (7) The Barrier, (8) The Breakthrough (Harding 27).

Stage 1, The Headless Infant, is the primordial state of awareness that all human beings start with. It involves feeling at one with the world as it is perceived. Things are taken at face value, without any mental projections obscuring the experience of the present moment. Babies do not identify with their faces reflected in a mirror, it is simply taken as what it is: a temporary visual phenomenon that is distinct from one's true identity of spacious emptiness. Harding says: "I have never been anything but this ageless, measureless, lucid and altogether immaculate Void" (Harding 11).

Stage 2, The Child, involves a mixture of pure, headless awareness and the beginnings of a mentally-constructed identity that is fueled by ideas from other people, not solely from one's own immediate experience of life: "At this stage you come near to making the best of both worlds—the unlimited non-human world you are coming from and the limited human world you are entering. All-too-briefly, you have in effect two identities going, two versions of yourself" (Harding 28).

Stage 3, The Headed Grown-up, involves increased identification with one's limited self, one's ego, to the point that one no longer feels as though one contains the world, but that one is a small entity contained within the world. Harding writes that at this stage we grow greedy, resentful, alienated, lonely, suspicious, frightened, defeated, tired, stiff, uncreative, unloving, and crazy because we lose our identification with our timeless, spacious identity and become identified with a small self that has all sorts of problems (Harding 29-30). This is the stage that most adult humans get stuck at. "We actually believe (contrary to all the evidence) that we are at 0 meters what we look like at 2 meters—solid, opaque, colored, outlined lumps of stuff. How can our life and our world stay sane if their very Centre has gone insane?" (Harding 30).

Harding asks the question: is it necessary for a developing human to pass through the pain of stage 3, or can it be bypassed? Harding's answer is yes, it is necessary: "In fact, there's no route from the Paradise of childhood to the Heaven of the blessed that doesn't lie through the Far Country, through some kind of Hell or at least Purgatory" (Harding 31). In other words, one must fully pass through delusion before achieving true clarity; one cannot skip around the pain of delusion and jump straight to clarity.

Harding puts it this way: "Really to lose our heads, we must first have them firmly in place... It is the precondition of a freedom that can be had no other way" (Harding 31). One must pass through the stages of childhood innocence through adult ignorance to then eventually re-establish a living, conscious identification with the clarity that was unconsciously experienced in childhood. T.S. Eliot's famous lines are apt to be quoted here: "We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time."

Stage 4, The Headless Seer, is achieved by turning one's arrow of attention towards oneself and consequently directly realizing one's inherent emptiness and spaciousness, which is not defined or limited by social or individual concepts. This is only possible if one "is willing to drop for a moment opinions about [oneself] based on hearsay and memory and imagination, and to rely on present evidence" (Harding 32).

Stage 5, Practicing Headlessness, is best described by Harding himself:

The repetition of this headless seeing-into-Nothingness till the seeing becomes quite natural and nothing special at all; till, whatever one is doing, it's clear that nobody's here doing it. In other words, till one's whole life is structured round the double-barbed arrow of attention, simultaneously pointing in at the Void and out at what fills it. Such is the essential meditation of this Way. It is meditation for the market-place, in fact for every circumstance and mood, but it may usefully be supplemented by regular periods of more formal meditation—for example, a daily sitting in a quiet place enjoying exactly the same seeing, either alone or (better) with friends. (Harding 37)

Stage 6 is called Working It Out and involves a further deepening of understanding of insights gleaned from the state of headlessness. An example of an insight that one could deepen at this stage is when one sees into one's own inner void, one realizes that the void encompasses all beings, and therefore all beings are fundamentally the same.

Stage 7, The Barrier, is a painful yet necessary stage because it involves the surrender of the ego's (often strong) will. The Western mystical tradition refers to this stage as The Dark Night of the Soul, which is a drastic purgative experience because the thing being purged is one's own heart, the seat of personality (Harding 52). Total self-surrender is required at this stage in order to move on to the eighth and final stage: The Breakthrough.

The purgation of stage 7 results in "a profound declaration of intent. It is the realization at gut level (so to say) that one's deepest desire is that all shall be as it is—seeing that it all flows from one's true Nature, the Aware Space here" (Harding 53). Harding says that ultimately, there is nothing one can do to bring about this breakthrough: "It's not a doing but an undoing, a giving up, an abandonment of the false belief that there's anyone here to abandon" (Harding 53). The ego-self must be lived to its fullest extent before it ceases to be needed as a function of the human psyche. The ego-self is put to various tests in the marketplace of regular human existence that gradually lessen its attachment to itself if the evolving self chooses to practice selfless action. The practice of self-surrender in the often-challenging marketplace of humanity progressively whittles away at the self until there is no more self left to lose.

Works Cited

Harding, D. E. On Having No Head: Zen and the Rediscovery of the Obvious. The Shollond Trust, 2014.