Glimpses of Truths That Transcend Cultural Distinctions

Published on November 20, 2019.

Last updated on November 20, 2019.

Written by Chad Timblin.

All humans across time and space share a fundamental nature that is unaffected by any degree of cultural variance. This fundamental human nature seems to include a tendency to seek truth. Each human individual seeks truth (in widely varying degrees of intensity and awareness) through their subjective filter of reality (i.e. their own selves). Rumi, a 13th-century Sufi poet, offers this perspective:

"All the hopes, desires, loves, and affections that people have for different things - fathers, mothers, friends, heavens, the earth, palaces, sciences, works, food, drink - the saint knows that these are desires for God and all those things are veils. When men leave this world and see the King without these veils, then they will know that all were veils and coverings, that the object of their desire was in reality that One Thing."

Rumi (1207-1273)

Rumi (1207-1273)

It is worth noting that my understanding of the distinction between a subjective human person and the common human nature that unites each individual person (i.e. a deeper level of identity than personhood) came directly from the great writings of Bernadette Roberts, an extraordinary Christian mystic with a contemplative orientation.

Words attributed to Krishna in a 1935 English translation of the Bhagavad Gita express a similar idea from a slightly different angle:

"No matter by what path men approach Me, they are made welcome. For all paths no matter how diverse lead straight to Me. All paths are mine, notwithstanding by what names they may be called. Even they who tread the path of the lower deities and imaginary gods and who pray to them for success through action—even these, say I, meet with reward, for they reap the success that comes from earnest application and industrious action. Through the laws of Mind and Nature, do their gods, real or imagined, answer them."

Krishna's revelation to Arjuna.

Krishna's revelation to Arjuna.

Perhaps the various things that Rumi mentions (fathers, mothers, friends, heavens, the earth, palaces, sciences, works, food, and drink) could be potential forms of the "lower deities" referenced by Krishna?

As you may well know, any word that is used to refer to the transcendent reality that supports all things is nothing more than a symbolic pointer to that 'One Thing' which can never be expressed in words. Keeping this in mind, please feel free to use whichever word(s) that most resonates with you and try to ignore any potential negative baggage that certain words may carry. For example, the word 'God' can turn a lot of people off due to negative experiences they had with a religious tradition that heavily emphasized a particular concept of God. Please pardon this imprecise use of language—there does not seem to be a 'best' word to use to refer to the ineffable, so within the context of this writing, words such as 'truth,' 'God,' 'Reality,' 'that One Thing,' etc. are interchangeable. (Other words that may also be used to refer to the ineffable: Intelligent Infinity, the Creator, All That Is, the Tao.)

Ralph Waldo Emerson published a poem called "Brahma" in the Atlantic Monthly in 1857. When he heard that many of his readers were perplexed by it, he chuckled and said, "Tell them to say 'Jehova' instead of 'Brahma' and they will not feel any perplexity."

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)

Krishna continues his testament to the ultimate universality of truth:

"After many lives, and with accumulated wisdom, the Wise Ones come to Me, knowing Me to be All. Such are called Mahatmas [i.e. great souls], and are rare and difficult to find by lesser men. And the others, who are drawn away through lack of understanding, to this deity, or that one, with various rites and ceremonies, find other gods. They find that which they seek, according to their natures.

But, knoweth this, O Arjuna—and note it well, for it is difficult of understanding among those who are bigoted, fanatical and narrow of mind and sympathy—the truth is this: that though men worship many gods, and images, and hold many conceptions of Deity, which they reverence as objects of worship—yea, even though these men seem utterly opposed to each other, and to Me—yet doth their faith arise from a latent and unfolded faith in Me.

Their faith in their gods and images is but the dawning of faith in Me; in worshipping these forms and conceptions, they wish to worship Me, although they know it not. And verily, say I unto you, such Faith and Worship, when honestly and conscientiously held and performed, shall not go unrewarded nor unaccepted by Me. Such men do the best possible to them, according to their light of dawning knowledge; and the benefits they seek, according to their faith, shall come to them, yea, even from Me. Such is my Love, Understanding and Justice."

Krishna asserts that the sincerity of one's heart is more important than the particular form of religion or spirituality they practice.

This does not mean that all spiritual practices are equally good. According to the Bhagavad Gita, sincerity of heart is the necessary prerequisite for producing spiritual fruit. Humans can produce a wide variety of "good" or "bad" fruits through their intentions and actions. All humans are drawn to thought and action by their internal Guiding Principle (i.e. their highest aspiration). This principle operates subconsciously if it is not known by the conscious aspect of one's mind. Whatever a being cares most about and takes to be the most important thing in existence, that is their God, and one will rise as high as their highest aspirations. David Foster Wallace put it well:

"Because here's something else that's weird but true: in the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship–be it JC or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles–is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. It's the truth. Worship your body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly. And when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally grieve you. On one level, we all know this stuff already. It's been codified as myths, proverbs, clichés, epigrams, parables; the skeleton of every great story. The whole trick is keeping the truth up front in daily consciousness."

Jean Bodin, a 16th-century French philosopher, expresses a message parallel to Krishna's through one of his fictional characters by the name of Senamus. Senamus says that religious variety is inevitable and "proposes an affective criterion of authenticity. He suggests that because no certain set of true beliefs or right behaviors can be identified, one must take the world as it is and accept sincere religiousness or piety—an inner quality of the heart—as sufficient where it ultimately counts—in the eyes of God."

Jean Bodin (1530-1596)

Jean Bodin (1530-1596)

Senamus "illustrates the modern turn to subjectivity..., wherein truthfulness [i.e. sincerity] makes do in the absence of an absolute ethic. This position shifts attention away from referential questions about the 'religious object' (about which consensus is not possible and therefore not necessary) to subjective matters about what characterizes the authentically religious person, and from what is true to what is an appropriate response to the ultimate reality to which all religions bear witness."

Through Senamus, Bodin "spells out the pluralistic implications of his single criterion of sincerity: 'I believe that all the religions of all the people, the natural religion which Toralba loves, the religion of Jupiter and the gentile gods, whom the Indians of the Orient and the Tartars cherish, the religion of Moses, the religion of Christ, the religion of Mohammed, which everyone pursues with his own rite, not with faked pretense but with a pure mind, are not unpleasing to eternal God and are excused as just errors, even though that which is best [but cannot be known with certainty] is the most pleasing of all.'"

I came across a piece of writing in my late grandfather's exercise room with the title "As Unto Me" (written by Roy Lessin). Lessin's words echo themes present in both Krishna and Senamus' statements, such as the primary importance of sincerity and integrity in the spiritual quest:

Others may not notice your efforts or give you recognition for something you've done. The credit may even go to someone else. Do it anyway, as unto Me, for I am pleased by your service and will honor your obedience.

There may be times when a job you have done will be rejected. Something you have prepared may be delayed or cancelled. Do it anyway, as unto Me, for I see all things and will bless the work of your hands.

You may do your very best but have your labors fail. You may sacrifice time and money to help someone and receive no words of appreciation. Do it anyway, as unto Me, for I am your reward and will repay you.

There may be times when you go out of your way to include others and later have them ignore you. You may be loyal on your job and still have someone promoted ahead of you. Do it anyway, as unto Me, for I will not fail you or make you be ashamed.

You may forgive others only to have them hurt you again. You may reach out to bless others only to have them take advantage of your kindness. Do it anyway, as unto Me, for I know your heart and will comfort you.

You may speak the truth but be considered wrong by others. You may do something with good intentions and be completely misunderstood. Do it anyway, as unto Me, for I understand and will not disappoint you.

There may be times when keeping your word means giving up something you would like to do. There may be times when a commitment will mean sacrificing a personal pleasure. Do it anyway, as unto Me, for I am your friend and will bless you with My presence.

Roy Lessin (1942-)

Roy Lessin (1942-)

Lessin articulates, in his own way, one of the central themes of the Bhagavad Gita: that one should not concern themselves with the fruits of their actions but should instead focus on living rightly, to the best of their knowledge and ability, in accordance with universal truth.

Discussing the nature of religion will never produce a final, definitive answer to the question, "What is religion?" Despite this, it can be worthwhile to consider various perspectives on the nature of religion because doing so can deepen one's appreciation of the beauty and diversity of humanity and creation as a whole.

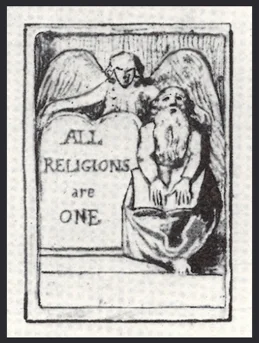

Many people who have thought deeply about the nature of religion came to the general conclusion that the root of each diverse expression of religion stems from the same source. William Blake called the source of all religious and philosophical ideas the "Poetic Genius," which is something akin to the human imagination.

An impression by William Blake (1757-1827) that says, "All Religions are ONE".

An impression by William Blake (1757-1827) that says, "All Religions are ONE".

William James, a 19th-century American philosopher of religion, provides this broad definition of religion:

"Were one to characterize the life of religion in the broadest and most general terms possible, one might say that it consists of the belief that there is an unseen order, and that our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves hereto."

Religions can be thought of as human constructions based on subjective experiences of objective truth (i.e. revelations). Many religions have their origin in an individual's (subjective) experience of universal truth. This revelation usually leads to the recipient translating their experience into some form of spiritual teaching, which is then shared to others and spread far and wide. William James viewed the basic experience which unified all religions as "a sometimes life-changing personal event in which one perceives the [interconnectedness] of all things as one unified whole."

Like biological species, religions naturally change over time (in healthy and unhealthy ways) due to numerous variables which are ultimately outside the control of any person or group of persons.

Diana L. Eck, a modern scholar of religion, says that religions are more like a river than a stone because humans and their environments are in a constant state of flux. All religious traditions will naturally change at varying rates through the course of history as humans (and cultures) evolve and adapt. One can think about this metaphor from another angle that perhaps goes a bit deeper. Rather than solely a river, religion could be analogous to a stone getting carried along by the current of a river. The stone can represent the innate drive to seek transcendent truth that all humans experience and the different positions that the stone briefly inhabits along its journey through the river of time can represent all of the different ways the human drive to seek truth manifests itself in the form of religious traditions.

The Ganges River in India.

The Ganges River in India.

Because of the virtually infinite degree of diversity amongst human persons, it could be said that the amount of adherents to any particular religion is ≥ 1. (By the way, this diversity amongst persons does not negate the existence of humanity's common nature because this nature exists beneath the level of personhood.)

No two persons have the exact same subjective experience of life, therefore it could be argued that in a sense, every single person who adheres to a religion adheres to a religion that is uniquely their own (to varying degrees of course). The numerous nuanced subjective perspectives of religion, and reality in general, are, necessarily and practically, simplified by broad labels which conveniently encompass large numbers of people. For example, each person out of the more than 450 million who identify as Buddhist today, practices a version of Buddhism that is uniquely their own due to their inherent subjectivity and unique window into the human experience.

The subjective nature of consciousness and religion should NOT imply that truth is ultimately relative or that all religions are equally good or bad. On the contrary, each and every religious belief and practice exists somewhere along a spectrum between absolute truth and absolute falsity. No one religion gets everything right or wrong. It's not important to attempt to actually place various religions on this imaginary spectrum; the point is to recognize that no religion has a monopoly on truth but that all (or at least most) religions have at least some access to truth, represented in various ways.

On a practical level, religions can serve as technologies for perceiving and knowing truth. Any religious system adopted for the (sincere) purpose of serving as a vehicle to help one orient oneself to truth should not be denigrated, because as long as the intention to seek and know truth is genuine, that drive will eventually bear spiritual fruit (at least according to Krishna, Senamus, and others). The only justification for seriously condemning a religious belief system is if that belief system causes a significant degree of demonstrable harm on any conscious being. All I really want to say about that is to encourage each person (myself included) to strive to listen to their genuine heart before casting judgement on others, but to also not be shy about condemning destructive religious behavior.

Each religious aspirant has the potential to eventually get to a point where clinging to a religious system is unnecessary. This phase in the journey can lead to a realization of all religions' inability to comprehensively contain truth. "Every religion is the product of the conceptual mind attempting to describe the mystery" says Ram Dass. The mystery of being can never be boxed in by the conceptual mind.

A popular Buddhist metaphor nicely illustrates the spiritual journey: one can liken religious practice to a raft that helps an aspirant get from one side of a river (i.e. ignorance) to the other side (i.e. a direct experience of truth or union with truth). Some people prefer rafts made out of wood while others prefer plastic rafts. You get the idea.

To reiterate, this article is not endeavoring to posit that all religions are equally true or valuable, or that in the final analysis they are all really saying exactly the same thing. Rather, the attempt is to explore the mysterious and seemingly universal human inclination to intuit, represent, and seek a transcendent dimension of reality. In other words, the goal is not to water down a multitude of religious ideas to one basic idea; the goal is to explore the possibility that the various examples quoted here may be referring to the same transcendent truths which ultimately exist beyond all representations and symbols.

Friedrich Schleiermacher, a German theologian who died in 1834, postulated this explanation for the origin of religion:

"Religion is the outcome neither of the fear of death, nor of the fear of God. It answers a deep need in man. It is neither a metaphysic, nor a morality, but above all and essentially an intuition and a feeling… Dogmas are not, properly speaking, part of religion: rather it is that they are derived from it. Religion is the miracle of direct relationship with the infinite; and dogmas are the reflection of this miracle. Similarly belief in God, and in personal immortality, are not necessarily a part of religion; one can conceive of a religion without God, and it would be pure contemplation of the universe; the desire for personal immortality seems rather to show a lack of religion, since religion assumes a desire to lose oneself in the infinite, rather than to preserve one's own finite self."

Here are some more relevant quotes from various religious and spiritual thinkers across time and space:

"God is a circle whose center is everywhere and circumference is nowhere." (Timaeus of Locris)

"Religion… is universal and it is one. We cannot possibly universalize particular customs and conventions; but the common element in religion can be universalized, and we may ask all alike to follow and obey it." (Paramahansa Yogananda)

Paramahansa Yogananda (1893-1952)

Paramahansa Yogananda (1893-1952)

"Despite such a notable gulf between East and West, and considerable varieties within each bloc, there is a strong undercurrent that seems to bring all religions, scattered so widely by time and geography, back together in a common fold. That is the consistent emphasis made by the authors in this book, that salvation—which in mythological language is located in the hereafter or in the idealized future—is attainable now, in this life. Both Hinduism and Buddhism are represented here as claiming the possibility of ultimate release in the midst of this life. The New Testament faith… and the theological development of Christianity… bring home the point that immortality is not 'more life after death,' but the realization of life in proper relation with God, the center of value, right here in this life. The reader will be struck by the amazing degree of consensus found in these faiths that are otherwise so much apart from one another. But that is, after all, precisely the essence of cross-cultural overview among these, the axial religions, that has enriched human experience down through the centuries." (from the intro to 'Death and Afterlife: Perspectives of World Religions' by Hiroshi Obayashi)

Also relevant, here's a summation of Aldous Huxley's Perennial Philosophy (highly influenced by Vedantic Hinduism):

- The phenomenal world of matter and of individualized consciousness—the world of things and animals and men and even gods—is the manifestation of a Divine Ground within which all partial realities have their being, and apart from which they would be nonexistent.

- Human beings are capable of knowing about the Divine Ground by inference; they can also realize its existence by a direct intuition, superior to discursive reasoning. This immediate knowledge unites the knower with that which is known.

- Man possesses a double nature, a phenomenal ego and an eternal Self, which is the inner man, the spirit, the spark of divinity within the soul. It is possible for a man, if he so desires, to identify himself with the spirit and therefore with the Divine Ground, which is of the same or like nature with the spirit.

- Man's life on earth has only one end and purpose: to identify himself with his eternal self and so to come to unitive knowledge of the Divine Ground.

Aldous Huxley (1894-1963)

Aldous Huxley (1894-1963)

What is the ultimate destination of the human journey towards God? No one can know ahead of time and language can hardly even begin to adequately reference this mystery, but it may be something like full and eternal union with God. Krishna puts it this way: "After many lives, and with accumulated wisdom, the Wise Ones come to Me, knowing Me to be All." How could it be any other way if God is the All in All? This mystery could also be loosely referenced as the merging of all apparent dualities and polarities (i.e. primordial, utmost unity), which is a perspective expressed by Ra in The Law of One:

"In truth there is no right or wrong. There is no polarity, for all will be, as you would say, reconciled at some point in your dance through the mind/body/spirit complex which you amuse yourself by distorting in various ways at this time. This distortion is not in any case necessary. It is chosen by each of you as an alternative to understanding the complete unity of thought which binds all things. You are not speaking of similar or somewhat like entities or things. You are every thing, every being, every emotion, every event, every situation. You are unity. You are infinity. You are love/light; light/love. You are. This is the Law of One."

What if the transcendent drive to seek and merge with truth that all humans seem to share is not exclusive to human beings? What if every particle of the fabric of reality is continuously, individually, and collectively evolving upwards to states of greater complexity? Humans currently exist on a plane of evolutionary development that is distinct from other planes/paths, such as the plant kingdom. Despite the distinction of different stages and branches of evolutionary development, the fundamental attribute of an inherent drive to perpetually grow is shared by both plants and humans, and possibly every other form of life in the entire universe. Another way to put this idea is this: Every aspect of the created spirals upward into greater complexity until there is no more any distinction between the Creator and the created.

Fractals are a striking way to visually represent infinity.

Fractals are a striking way to visually represent infinity.

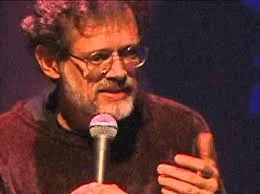

The great American bard Terence McKenna contributed to this speculative dialogue with an idea he dubbed "The Transcendental Object at the End of Time." Terence postulated that the universe is continuously increasing in novelty and complexity at an exponential rate and that this constant increase of novelty will eventually culminate in a state of maximal novelty commonly referred to as "the singularity."

Terence McKenna (1946-2000) would often wax poetic about his intuition that the universal agenda is to produce maximal novelty through continuous, progressive evolution.

Terence McKenna (1946-2000) would often wax poetic about his intuition that the universal agenda is to produce maximal novelty through continuous, progressive evolution.

Related Readings:

"The Ecumenical Council" by Salvador Dali represents the "interconnectedness" of the Omega Point.

"The Ecumenical Council" by Salvador Dali represents the "interconnectedness" of the Omega Point.

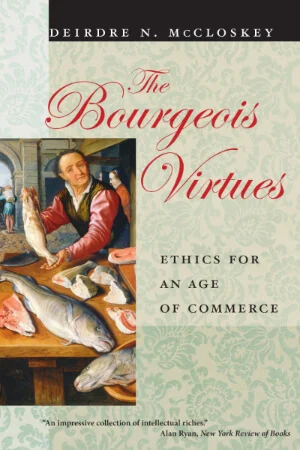

I'll end this somewhat long musing with a more modern quote: an excerpt from Deirdre McCloskey's The Bourgeois Virtues:

"In other words, we humans, even we bourgeois humans, cannot get along without transcendence - faith in a past, hope for a future, justified by larger considerations. If we don't have religious hope and faith, we'll substitute hope and faith in art or science or national learning. If we don't have art or science or national learning or Anglicanism, we'll substitute fundamentalism or the Rapture. If we don't have fundamentalism or the Rapture or the local St. Wenceslaus parish we'll substitute our family or the rebuilt antique car. It's a consequence of the human ability to symbolize, a fixture of our philosophical psychology.

We might as well acknowledge it, if only to keep watch on transcendence and prevent it from doing mischief, as did once a Russian hope for the Revolution and as now a Saudi Arabian faith in an Islamic past. The Bulgarian-French critic Tzvetan Todorov, who has seen totalitarianism, warns that 'democracies put their own existence in jeopardy if they neglect the human need for transcendence.' Michael Ignatieff put it well: 'the question of whether… the needs we once called religious can perish without consequence… remains central to understanding the quality of modern man's happiness.' Evidently the answer is no, a religion cannot perish without consequences. There are bad consequences and there will be more. That is not a reason to return to the older sureties, it is a reason to take seriously the transcendent in our bourgeois lives."

If you made it this far, thank you for joining me in the endless, fascinating, speculative, and sometimes absurd quest to discuss the ineffable.

Actually, I can't resist ending with some inspired words that flew from the heart and pen of the mystical Walt Whitman:

"This is what you shall do; Love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to every one that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God, have patience and indulgence toward the people, take off your hat to nothing known or unknown or to any man or number of men, go freely with powerful uneducated persons and with the young and with the mothers of families, read these leaves in the open air every season of every year of your life, re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul, and your very flesh shall be a great poem and have the richest fluency not only in its words but in the silent lines of its lips and face and between the lashes of your eyes and in every motion and joint of your body."

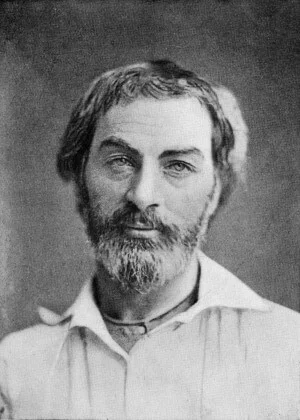

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

I do not interpret Whitman's words to be primarily prescriptive (i.e. as a call to emulate his particular mode of being); instead, I take them as his way of saying something like, "Do not be afraid to trust and follow your own soul as you explore the mystery of being!"

In the face of the vast mystery of being, there seems to be no other choice than to simply be what one naturally is and to strive to accept whatever comes as the present moment continues to offer new phenomena for conscious beings to experience and ponder.

I wish you, reader, nothing less than the very best in your unique yet universal journey to an unknown destination.