Whitman the Rishi

Published on May 20, 2017.

Last updated on May 20, 2017.

Written by Chad Timblin.

This paper will attempt to highlight some connections between mystical elements expressed in Walt Whitman's poem, Song of Myself, and two classic Indian texts: the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita.

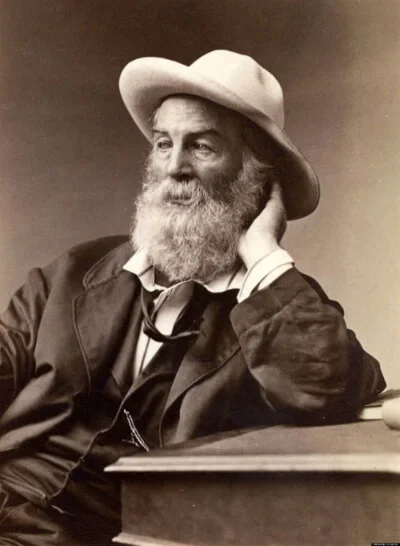

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

What is a rishi and how can Walt Whitman be considered one? Rishi translates literally to "seer" and traditionally refers to the original authors of the Vedas—ancient Indian religious texts which inform the basis of many Hindu cultures (the Upanishads are the concluding portions of the Vedas) (Yogananda 44). This can't be known for sure of course, but one perspective is that the authors of the Vedas accessed knowledge about the universe through introspective explorations of their own consciousness. In a similar manner, Whitman accessed his revelations through communion with his own Self (i.e. consciousness), which he discovered is fundamentally identical to the Self of all beings in the universe: "In all people I see myself, none more and not one a barley-corn less, / And the good or bad I say of myself I say of them"

(Whitman 35).

Whitman's friend, Richard Maurice Bucke, remarked that Whitman "appeared to like all the men, women, and children he saw"

(Bucke 221). This quote correlates with an Upanishadic description of the knower of the Self: "He who sees all beings in the Self, and the Self in all beings, hates none"

(Prabhavananda 4). An all-inclusive acceptance of every being, just as they are, seems to be a natural repercussion of directly realizing the thread of inherent sameness that connects each and every being. Whitman celebrates this fundamental unity in the opening lines of his poem, Song of Myself: "I celebrate myself, and sing myself, / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you"

(Whitman 21). Shortly after this proclamation, Whitman invites the reader to explore the reality of their unconditioned, internal Self:

Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

You shall possess the good of the earth and sun, (there are millions of suns left,)

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand, nor look

through the eyes of the dead, nor feed on the spectres in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from your self. (Whitman 22)

The omnipresent Self that pervades Song of Myself could be Whitman's vehicle for hinting at the same 'thing' that the Hindu notions of Atman, the inner spirit, and Brahman, the Divine Absolute, refer to.

According to the Upanishads, Atman, Brahman, and the Self are fundamentally one (Prabhavananda 3). There are various interpretations of what Atman and Brahman refer to, but within the context of this paper, they will be accepted as ultimately pointing to the same unitive source of all existence. Whitman recognized the unchanging, eternal Self and asserted that the numerous varieties of fluctuating external forms (people, dates, discoveries, societies, sicknesses, etc.) and internal states (depressions, exaltations, etc.) "are not the Me myself"

(Whitman 23). In other words, Whitman distinguished between the eternal Self and the numerous temporary costumes worn by the temporary, egoic self.

All of the seemingly endless dualistic and relative forms which manifest in the physical world fall under the umbrella of maya, which according to ancient Hindu rishis, ultimately stems from the outwardly manifesting, creative female energy inherent to the universe: Shakti (Yogananda 261). The veil of maya often causes the delusion that manifest things are fundamentally separate from their unmanifest, eternal source beyond creation (i.e. Atman/Brahman/the Self). Manifest things come and go according to Shakti's divine play of creation: lila (Yogananda 399). Shakti, often portrayed as the Goddess Kali, dances on top of the infinite canvas of the unmanifest eternal Self which pervades the inside and outside of all things. In some Hindu belief systems, the unmanifest aspect of the cosmos is commonly portrayed as the deity Shiva in a supine position. Whitman also touches on the nature of manifest things: "These come to me days and nights and go from me again,"

and remarks that they do not affect the objective awareness of the Self: "Apart from the pulling and hauling stands what I am, ... Both in and out of the game and watching and wondering at it"

(Whitman 23).

What is 'the game'? Could it be all that ensues from the relationship between the unmanifest Divine Absolute (Shiva) and the outwardly manifesting creative force (Shakti/Kali)? The game remains a mystery to most, but perhaps not to the enlightened rishi. Dualistic notions of reality certainly appear to have some validity when existence is taken at face value; however, Song of Myself and the Upanishads proclaim that this apparent duality is a delusion, a veil covering the inherent oneness of reality. "I and this mystery here we stand"

says Whitman in an apparently dualistic statement of fact (Whitman 22). In this context, "I" seems interchangeable with Self, and "mystery" could be analogous to Brahman/the Divine Absolute. The next lines in Whitman's poem succinctly brush away any dualistic notions: "Clear and sweet is my soul, and clear and sweet is all that is not my soul"

(Whitman 22). If the soul and anything that initially seems to exist outside of the soul have the same fundamental characteristics, then they are actually one and the same. Paradoxically, perhaps it could be simultaneously true that everything is the soul and nothing is the soul. "Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself, / (I am large, I contain multitudes)"

(Whitman 68).

Whitman elaborates on all of the apparent dualities that he accepts as being a part of the Self: "I am the poet of the Body and I am the poet of the Soul, / The pleasures of heaven are with me and the pains of hell are with me... I am not the poet of goodness only, I do not decline to be the poet of wickedness also"

(Whitman 36, 38). Whitman realized that every single aspect of the cosmos, from the small to the large, is equally a part of the universal Self. It is irrelevant whether or not a particular aspect of the Self appeals to the lowercase, egoic self. In order to face reality without distortion, one must accept and admit all aspects of oneself, as Whitman did: "Evil propels me and reform of evil propels me, I stand indifferent"

(Whitman 38). Perhaps the "I" that stands indifferent is the deeper, universal Self? This Self cannot be summed up in words—at most it can be poetically hinted at: "I pass death with the dying and birth with the new-wash'd babe, / and am not contain'd between my hat and boots"

(Whitman 26). This omnipresent Self was referred to by Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita: "There is nothing that exists separate from me, Arjuna. The entire universe is suspended from me as my necklace of jewels"

(Easwaran 153).

A major theme expressed in Song of Myself is the idea that the seemingly mundane, physical aspects of reality are just as important as the more ethereal aspects of reality, which are commonly referred to as soul and spirit. "I have said that the soul is not more than the body, / And I have said that the body is not more than the soul, / And nothing, not God, is greater to one than one's own self is"

(Whitman 66). In a somewhat ambiguous, mystical aphorism, the Isha Upanishad affirms the value of accepting every aspect of one's Self: "Those who worship both the body and the spirit, by the body overcome death, and by the spirit achieve immortality"

(Prabhavananda 5). Bucke expressed Whitman's embodiment of this Upanishadic proclamation:

The simple and commonplace with [Whitman] included the ideal and the spiritual. So it may be said that neither he nor his writings are growths of the ideal from the real, but are the actual real lifted up into the ideal. With Walt Whitman his body, his outward life, his inward spiritual existence and his poetry were all one; in every respect each tallied the other, and any one of them could always be inferred from any other (Bucke 218-219).

According to Bucke, the central teaching of Whitman's writings and life is "that the commonplace is the grandest of all things; that the exceptional in any line is no finer, better or more beautiful than the usual, and that what is really wanting is not that we should possess something we have not at present, but that our eyes should be opened to see and our hearts to feel what we all have"

(Bucke 224).

The title and content of Song of Myself imply music and dance, which in turn imply vibration. The universal vibration is said to be OM:

The syllable OM, which is the imperishable Brahman, is the universe. Whatsoever has existed, whatsoever exists, whatsoever shall exist hereafter, is OM. And whatsoever transcends past, present, and future, that also is OM. All this that we see without is Brahman. This Self that is within is Brahman (Prabhavananda 73).

In reference to his soul (i.e. Self), Whitman says that he only likes the hum of its valved voice (Whitman 24). What could the hum of the Self be? Ultimately, nothing other than the universal voice, OM. The Mandukya Upanishad states that the Self is one with OM (Prabhavananda 73). In section 26 of Song of Myself, Whitman describes a variety of sounds he hears in the world: bravuras of birds, a bustle of growing wheat, the human voice, the steam whistle, and many more. "I hear all sounds running together, combined, fused"

says Whitman (Whitman 42). All sounds are contained in and sustained by OM. Bucke had this to say about the poet's level of awareness:

I believe all the poet's senses are exceptionally acute, his hearing especially so; no sound or modulation of sound perceptible to others escapes him, and he seems to hear many things that to ordinary folk are inaudible. I have heard him speak of hearing the grass grow and the trees coming out in leaf (Bucke 216).

Maybe it is possible that Whitman literally heard the bustle of growing wheat that he mentions hearing in Song of Myself? Though it seems more likely that Whitman did not literally hear very subtle things like the grass growing—rather, he could have meant that he "heard" their essence by experientially realizing his deep connection to them. Who knows?

A central teaching expressed in the Bhagavad Gita ("The Song of God") is karma yoga, the yoga of works. Krishna teaches Arjuna that inner renunciation is the only true renunciation. This means that one should not be attached to the potential fruits of any action, good or bad, but should offer each action as a sacrifice to the Supreme Spirit in a state of equanimous detachment. The Isha Upanishad opens with an affirmation of this teaching:

Life in the world and life in the spirit are not incompatible. Work, or action, is not contrary to knowledge of God, but indeed, if performed without attachment, is a means to it. On the other hand, renunciation is renunciation of the ego, of selfishness—not of life. The end, both of work and of renunciation, is to know the Self within and Brahman without, and to realize their identity. The Self is Brahman, and Brahman is all (Prabhavananda 1).

Whitman affirms the truth that inner renunciation leads to a detached and equanimous state of consciousness: "Have you heard that it was good to gain the day? / I also say it is good to fall, battles are lost in the same spirit in which they are won"

(Whitman 34).

Here's another way Krishna divulged the truth of each being's identity to Arjuna: "I am the true Self in the heart of every creature, Arjuna, and the beginning, middle, and end of their existence"

(Easwaran 185). The Self is performing a cosmic song and dance by manifesting itself as every particle of existence. It is the beginning and end of all things: "Not a person or object missing, / Absorbing all to myself and for this song"

(Whitman 29).

Another form of yoga espoused by Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita is bhakti yoga, the yoga of devotion: "They for whom I am the supreme goal, who do all work renouncing self for me and meditate on me with single-hearted devotion, these I will swiftly rescue from the fragment's cycle of birth and death, for their consciousness has entered into me"

(Easwaran 208). Every being in the universe is animated by the creative weaving of the Self. Many beings are not conscious of this reality, though their lack of awareness does not negate the existence of the Self. Simply by existing contentedly as oneself, one honors the Self that is the source of all—though being aware of the Self allows one to consciously honor its existence through devotion and surrender in one's own way.

Whitman lists many different forms of the universal Self and concludes: "And these tend inward to me and I tend outward to them, / And such as it is to be of these more or less I am, / And of these one and all I weave the song of myself"

(Whitman 33). Whitman was aware of his true nature of deathlessness: "I acknowledge the duplicates of myself, the weakest and shallowest is deathless with me"

(Whitman 59). Whitman could claim deathlessness because he knew that all phenomenal forms, including himself, ultimately stem from the universal Self which constantly expresses itself in numerous variations. Life and death are cyclically intertwined as equal expressions of the Self's creativity: "The smallest sprout shows there is really no death, / And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it, / And ceas'd the moment life appear'd / All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses, / And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier"

(Whitman 25).

Krishna illuminating Arjuna.

Krishna illuminating Arjuna.

A central idea expressed in Song of Myself, the Upanishads, and the Bhagavad Gita is that there is a universal, unchanging Self at the heart of every being. Many names have been used to hint at this Self, so one should not worry too much about which particular name is used, because the same reality is being referenced. As the Rig Veda states: "Truth is one, sages call it by many names."

The most words can do is hint at truths that one can discover through direct experience.

Works Cited

Bucke, Richard Maurice. Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 2009. Web.

Easwaran, Eknath. The Bhagavad Gita. Berkeley, CA: Nilgiri Press, 2007. Print.

Prabhavananda, and Frederick Manchester. The Upanishads: Breath of the Eternal. Hollywood, CA: Vedanta Press, 1983. Print.

Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. New York: Book-of-the-Month Club, 1992. Print.

Yogananda, Paramahansa. Autobiography of a Yogi. Los Angeles: Self-Realization Fellowship, 1998. Print.