William James' Conceptual Framework for Studying Mystical Experiences

Published on April 23, 2019.

Last updated on April 23, 2019.

Written by Chad Timblin.

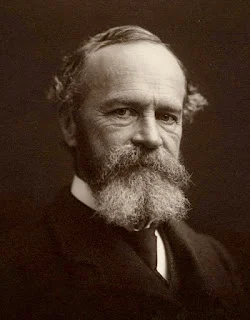

William James, a prominent 19th-century psychologist and scholar of religion, offered some conceptual frameworks to aid in the understanding of mystical experiences. James was self-admittedly not a mystic himself and made sure to clearly draw a distinction between first-hand knowledge and second-hand knowledge: "My own constitution shuts me out from [the enjoyment of mystical states] almost entirely, and I can speak of them only at second hand" (James 328). In other words, James was an outsider to mystical experiences looking in with his analytical mind with the intention to make some sense of the mysterious nature of mystical experiences.

William James (1842-1910)

William James (1842-1910)

Despite James' personal lack of mystical experiences, he viewed them with respect—as authentically real and of paramount importance to the existence of religion: "One may say truly, I think, that personal religious experience has its root and centre in mystical states of consciousness" (James 328). According to James, mystical experiences are the deepest form of religious experience because they involve some form of experiential communion with a reality transcendent to an individual. Contact with a dimension of reality deeper than what is immediately available to the conventional senses often produces modifications in the inner lives of individuals who have these types of experiences. For example, a Christian contemplative monk may actualize greater degrees of humility after experiencing the temporary suspension of his ego during a mystical experience that involved communion with what he would call God.

William James articulated four main qualities of mystical experiences: ineffability, a noetic quality, transiency, and passivity. According to James, the presence of the first two qualities, ineffability and a noetic quality, is essential and will qualify an experience as mystical. The latter two qualities, transiency and passivity, are less common and non-essential qualities, but nevertheless notable aspects to many mystical experiences.

The ineffability of mystical experiences means that they defy verbal expression. This is widely reported by countless people who have some type of mystical experience. Within the confines of conventional human language, this characteristic is a negative characteristic because it refers to the lack of language's ability to accurately represent the experiential mystical dimension. James compares mystical experiences to emotions because both emotions and mystical experiences must be directly experienced to be known. One cannot articulate a description of sadness and expect the listener to grasp the experience if he or she has not experienced sadness directly for themselves. In the words of William James: "[The mystical experience] cannot be imparted or transferred to others" (James 329).

The second essential quality to mystical experiences is a noetic quality. James writes that mystical experiences give the experiencer access to "states of insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect" (James 329). In other words, subjects of mystical experiences often report that the experience allowed them to see truths about themselves and reality that were not previously known.

A third common, although non-essential, characteristic of mystical experiences is transiency. "Mystical states cannot be sustained for long," says James. In his estimation, the average length of a mystical experience ranges from thirty minutes to two hours (James 329). One's sense of the passage of time is often highly affected during a mystical experience. For example, one second of clock-time could feel like an eternity to the person having a mystical experience.

Passivity is the fourth characteristic of mystical experiences that James delineates. It is not inherent to all mystical experiences, but it is common. James says that whether or not a mystical experience was coaxed into existence with proactive actions, once the experience sets in "the mystic feels as if his own will were in abeyance, and indeed sometimes as if he were grasped and held by a superior power" (James 330).

There are countless methods designed to cultivate altered or mystical states of consciousness, but they can only take one so far. At most, methodical techniques enacted with the intention of coaxing a mystical experience into existence seem to be able to prepare the ground for such an experience. Traditionally, this involved cultivating a holistically wholesome life. The actual mystical experience usually alters the individual experiencer more profoundly than he or she could alter themselves using solely their own will and limited powers. James observed this phenomenon: "Some memory of [the content of mystical experiences] always remains, and a profound sense of their importance. They modify the inner life of the subject between the times of their recurrence" (James 330).

For example, Christian mysticism is a mystical tradition that contains theories and techniques designed to help one reach states of mystical insight. The theory put into practice by Christian mystics is that negating lesser, sensual pleasures opens up the possibility of experiencing deeper, more subtle and profound truths. The fundamental practice to achieve oneness with God in the Christian mystical tradition is meditation ("the methodical elevation of the soul towards God") (James 351). Conventionally, the Christian mystic practitioner cultivates detachment from the five externally-oriented senses in order to be able to more clearly discern the nuances of the inner world (i.e. the soul's communion with God). A key component to Christian mystical experiences is a temporary negation of self that allows for one to be "awake in God"—this is known as the "orison of union." Paul said: "Only when I become as nothing can God enter in and no difference between his life and mine remain outstanding" (James 362).

Contemplating in a secluded forest.

Contemplating in a secluded forest.

James theorized that the universal "great mystic achievement" is to overcome barriers between the individual and the absolute (James 362). According to James, this fundamental goal is shared and expressed in various ways by numerous mystically-oriented religious and philosophic traditions, such as: Hinduism, Neoplatonism, Sufism, Christian mysticism, Whitmanism... (the list goes on) (James 363).

Works Cited

James, William. The Varieties of Religious Experience. Barnes and Noble Classics, 2004.